Memo #10: Rediscovering Rural Main Streets

By: David Paterson and Kieron Hunt, FBM Planning Studio

When a secondary highway doubles as your community’s main street, what are the tools available and relationships needed to make it walkable and vibrant? What do placemaking and small business support look like in a rural main street context?

Main Street in Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia

Pre-COVID, the pressing nature of these questions encouraged us to form the Nova Scotia Main Streets Initiative. We worked with the communities of Elmsdale, St. Peter’s and Westville (each with populations under 5,000 people) to identify opportunities and define specific challenges faced in these small communities around their main streets. The results of our research and discussions led to the creation of a Workbook, with a set of community-enabling approaches for rural and small town main streets.

Now confronted with the pandemic, the spaciousness and social connectedness of Main Streets in rural communities is even more important to consider. In terms of walking, cycling, local businesses, and gathering places, there are good bones in rural communities. A few key changes in our thinking can make rural main streets work – with the needed critical mass and mix of businesses and destinations.

Main Street in Elmsdale Village, East Hants, Nova Scotia

The Rural Lens

Like many other provinces, Nova Scotia is dotted with historic communities, tending more towards populations of 5,000 than 50,000. Nova Scotia’s rural communities have long histories, often associated with fishing, mining, forestry and manufacturing. There is an urban-rural divide, as cities like Halifax and its suburbs see population growth and an increased cost of housing, while rural areas continue to see declining populations and fewer working age adults. In rural areas, this comes with service delivery challenges for municipalities, and other issues including high rates of physical disability.

In recent years, part of Nova Scotia’s response has been a push to diversify economies, establish high speed internet or fibre optic networks, and focus on quality of life to attract new residents and younger families, especially in knowledge-based or mobile industries. With COVID-19, we are seeing signs of a potential “urban exodus,” as more people who are able to work remotely look to relocate outside cities. This is even more reason to think again about the role of main streets in smaller communities.

The Nova Scotia Main Streets Initiative, like Bring Back Main Streets (BBMS), is guided by a belief that examining main streets can help us better understand quality of life in rural areas, and that involving multiple partners and stakeholders is important in helping to make main streets a part of sustainable communities. Main streets are where multiple rural issues come together, including transportation, walkability, accessibility, social connection, public space, shops and services, housing, and entrepreneurship.

Main street acts as the “front yard” of rural communities and a place to promote local business and community identity. Rural communities often have strong senses of identity and social connectedness. While these are qualities that ought to play out on unique and memorable main streets, there are obstacles as well.

Main Street in St. Peter’s, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

Challenges for Rural Main Streets

Main streets are often experienced as places to drive through rather than destinations in and of themselves. On main streets, multiple business or civic locations may be within a few minutes walk of one another, but trips are usually by vehicle because the walking experience is poor and the driving culture is prevalent. Competition from big box sprawl has also taken a toll on business viability along main streets, as outlined in BBMS Memo #8.

The experience of main street can be haphazard, partly as a result of the division of jurisdictions, the varied property ownership, and overall focus on parking and the vehicle experience. In Nova Scotia’s case, main streets are often a short stretch of secondary highway infrastructure where the speed limit drops to 50 km / hr but the roadway design remains largely the same. In most cases, roadways are a provincial responsibility, while sidewalks and crosswalks, where they exist, are the responsibility of the village or municipality. The resulting physical design has proven to be a challenge for active transportation, accessibility, and safety. Sidewalks and crosswalks often don’t match desired walking routes and destinations; shops, amenities, housing, and green spaces are interspersed with surface parking and vacant lots that detract from the walking experience.

Lack of residential density near rural main streets is another challenge. In contrast to comparatively denser urban neighbourhoods, many people in rural communities live in settlements that may be several kilometers away from a main street. However, with aging seniors, as well as changing preferences among working age populations, there is an increasing demand for accessible and walkable housing options. This set of preferences, along with a desire for supporting local entrepreneurs in walkable downtowns, paves the way for a new recognition of strengthening main streets and the neighbourhoods they serve.

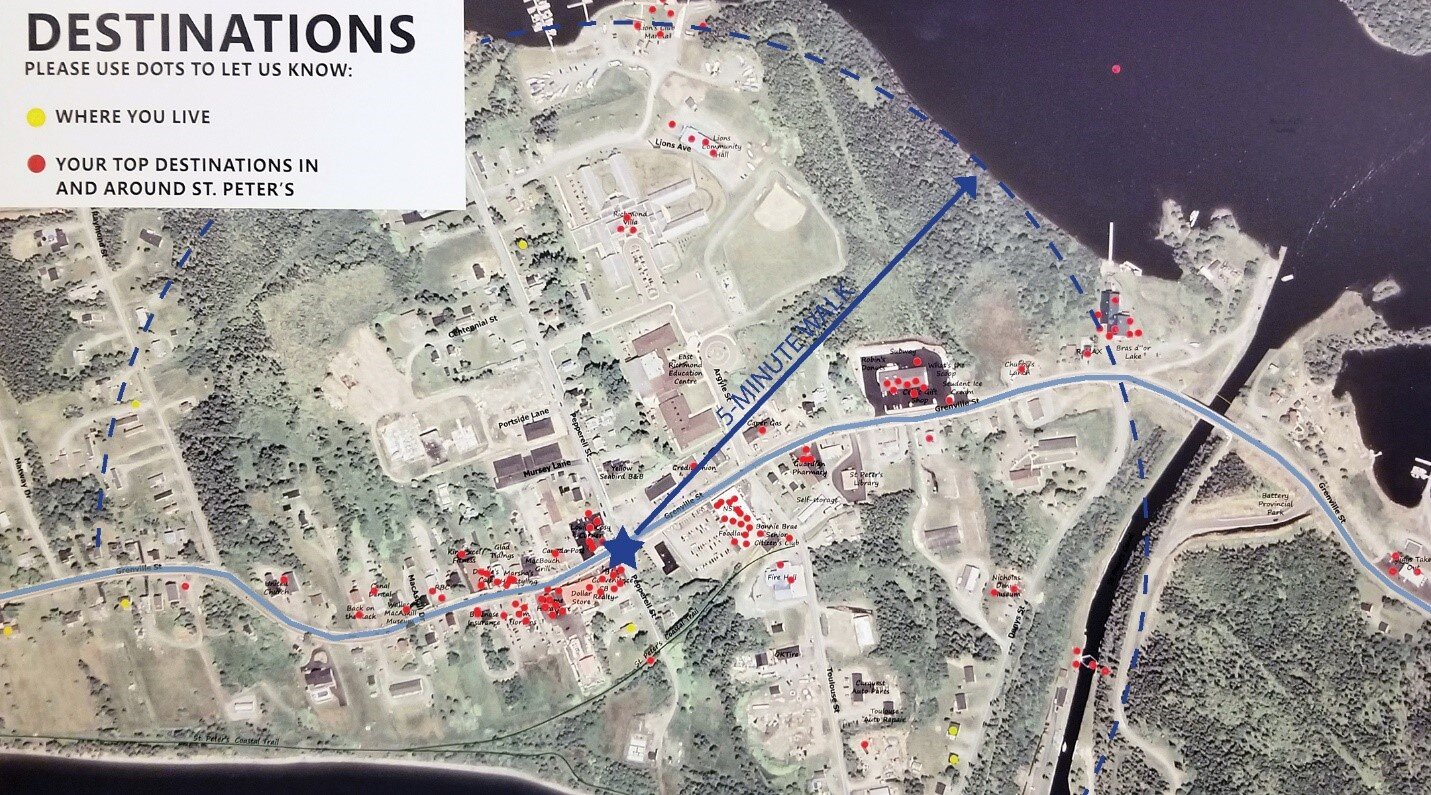

From engagement in St. Peter’s: a cluster of destinations on and near the highway that passes through the community. (from FBM’s Nova Scotia Main Streets Initiative Workbook)

Differentiating Rural Main Streets from the Highway

Within the provincial roadway network, Community Main Street Districts could be defined and designated as a focus area for accessibility, walking, and cycling improvements, while updates to municipal planning strategies and local land-use by-laws can cluster development to strengthen these areas in the long run. Vacant “opportunity sites” are often found on main streets, and can become new anchors for development, businesses, or civic amenities to stimulate energy among more historic buildings. Gateway moments for drivers are also key for defining the beginning of a community’s main street, as are developing parking and wayfinding strategies.

Towards Tactical Ruralism

Urban main streets tend more often to be the focus of placemakers, and the popularized planning term tactical urbanism seems to unnecessarily exclude rural communities. Yet, rural centres have always been active in taking community ownership of the street and adjacent public spaces. There is an opportunity for knowledge transfer between rural and urban placemakers towards new forms of tactical ruralism, or villagism. For communities in Nova Scotia, the pandemic has accelerated the momentum for exploring tactical options to calm traffic, support walkability, and enhance local business and community gathering.

Some of the focus areas and lessons learned from the Nova Scotia Main Streets Initiative include:

Pedestrianization – there is a latent desire to walk between destinations, including to park the car and walk along main street.

Accessibility and safety – an aging population needs to be better accommodated for trips from home to destinations, including businesses, services and public spaces.

Quality of life and attracting residents – main streets are the front yard of communities, and can be key in attracting new populations to set down roots, both as new residents and entrepreneurs.

Breaking down silos between advocates – the goals are often the same, whether groups advocate on behalf of parents, seniors, economic development, public space, active transportation, recreation or community health and well-being.

Breaking down silos between government bodies – to achieve streetscape design that recognizes that there is space for vehicles, active transportation, local business support and community placemaking to be accommodated.

Spaciousness – there is casually forgotten space on and along rural main street that can activated or re-purposed.

Local identity – showing genuine community identity by applying tactical ruralism can be a point of difference to make main streets memorable versus the generic big box shopping experience.

Entrepreneurship – main streets are the place to unleash local entrepreneurial creativity and freedom of expression.

Community connection – as “everyone knows everyone” in a small town, there are possibilities for small groups and multiple levels of government to come together to get things done.

Main Street in the Town of Westville, Nova Scotia

The Time to Rediscover Rural Main Streets

Canada is a country that was largely built around small towns and rural communities. Yet, main streets have often been left behind in the chase for urban glory and the new shiny retail toys and shopping centres. The pandemic has shone a light on how important rural main streets are to local communities’ social, cultural and economic well-being. Rural businesses have struggled during the pandemic, and yet have continued to give back to their communities during this difficult time. Now is the time to reciprocate and invest in rural main streets to create safer streets, social centrepieces and new entrepreneurial opportunities.